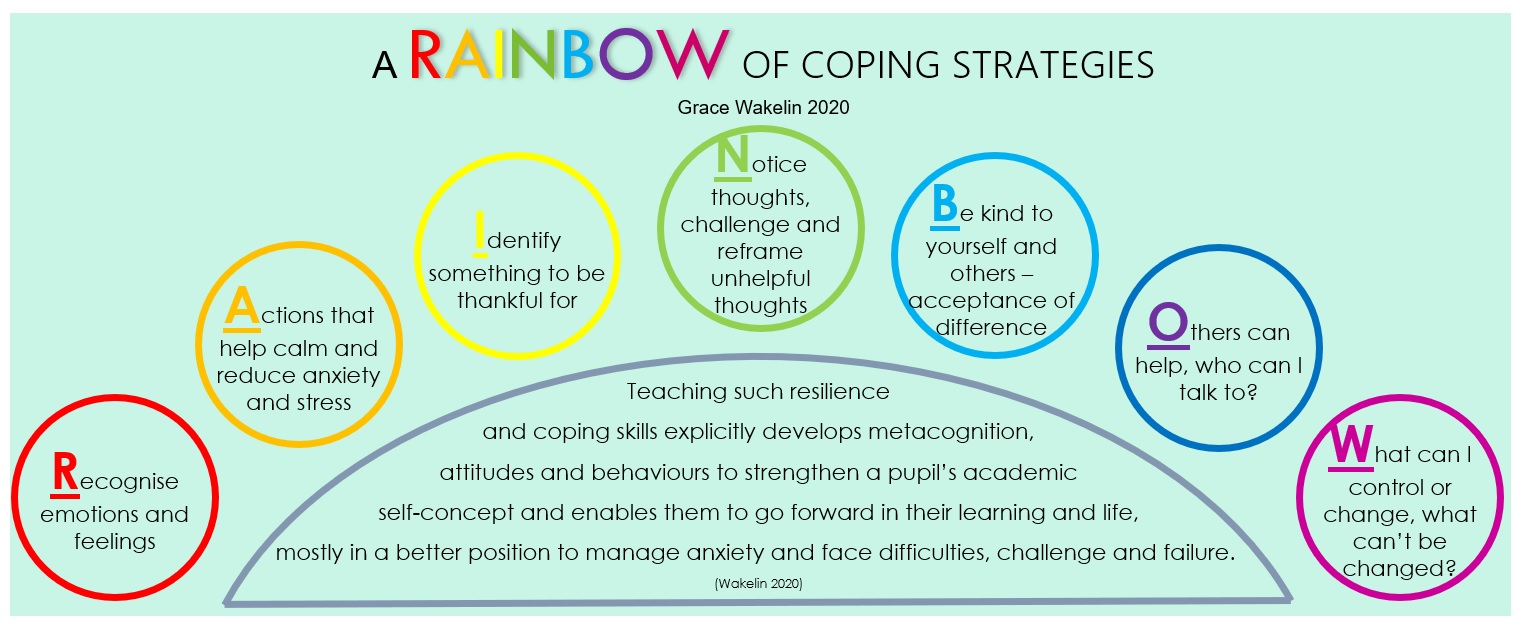

The research study, outlined in my previous post, identified strategies that may help develop protective factors in young learners. These will in turn lead to a stronger self-efficacy and resilience when facing challenges. I have arranged these as, a RAINBOW of coping strategies, that can be taught and modelled at home and school.

The full research study can be found at the link below

A rainbow is a symbol of hope and there are many quotes using a rainbow, rain and storms as a metaphor for life, including from Oscar Wilde “When it rains look for rainbows when it’s dark look for stars”. We develop resilience by learning to cope with, adapt to and move on from difficult situations.

Dyslexia or a specific learning difference is a life-long challenge to cope with. Consequently, when life throws additional challenges, having developed strategies to exercise resilience, these challenges can be worked through. It is important to note that individuals can still display sadness, self-doubt and anxiety in the face of difficulty, challenge and mistakes. However, it is the resilience developed, the coping strategies they can trigger, the ability to notice unhelpful thinking, challenge it and reframe, that enables them to cope, adapt and carry on.

Recognise my feelings and emotions

The word emotion comes from a Latin word meaning ‘move’. Feelings and emotions can ‘move us’ to react or act in a certain way. For example, fear may warn us about possible danger and cause us to take action to protect ourselves. Guilt may cause us to reflect on something we have done wrong and put it right. Anger or frustration can give us the confidence to advocate for what is right and, sadness due to losing a pet or family member can move us to create memories of them.

It is important to be okay with these emotions, they are natural responses to adversity and difficult situations. However, how long we stay with those emotions will depend on the situation, but then having the ability to cope, adapt and move on is essential.

The effect of Anxiety on learning

Anxiety can negatively impact the execution of tasks, problem-solving, self-regulation, cognitive processing and memory function (Everson et al 1994, Moran 2016). It can develop in children and young people who find learning difficult, and consequently, these negative effects lead to continued difficulty in learning. When faced with low marks, failure and mistakes, it requires a strong sense of self-efficacy to stay motivated (Bandura 1997). When overwhelmed by self-doubt and adversity quality of thinking is affected, which in turn will affect achievement.

The brain responds to anxiety and stress stimuli with the amygdala triggering our fight or flight response. The stress hormone cortisol is then released, which affects memory function and cognitive processing (McEwen & Morrison 2013). This results in difficulty to think clearly, problem-solve and concentrate, particularly if this stress response is switched on for a lengthy time.

We can learn to manage and control this stress response by developing these coping strategies.

Actions that will help calm me

Exploring practical ways to calm and relax can help lower anxiety and reduce stress to reverse the fight or flight stress response. We need to reverse this response to think more clearly about the situation or difficulty. Children can, from a young age, learn what will help them to feel calmer.

Below are some organisations providing help and support

https://www.headspace.com/meditation/breathing-exercises

https://www.barnardos.org.uk/blog/coping-anxiety

Some different activities to try

- Breathing techniques

- Colouring, painting

- Puzzles, building, construction

- Getting outside, play in the garden, walk, jump on a trampoline

- Imagine being in a special place

- Listening to music, dancing, singing

- Talking to a pet

- Squeezing a stress toy, watching a lava lamp

- Having a weighted blanket

Identify something to be thankful for.

There is debate on whether resilient thinking leads to positive emotion or positive emotion and thinking is a factor in enabling individuals to cope and demonstrate resilience when faced with difficulties. Research demonstrates how positive emotion has a regulating effect on negative emotion and supports developing effective coping strategies and resources when faced with adversity. Gratitude tracking has been strongly connected to well-being and promoting resilience (Tugade & Fredrickson 2004). Having an appreciation for things others do, for who others are, and for the little things in life.

Try a gratitude tracker or journal, there are some available to download for free or design one of your own.

How Many Positives Activity Sheet (youngminds.org.uk)

https://www.elsa-support.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Weekly-gratitude-and-emotions-tracker.pdf

Notice my thoughts, challenge and reframe unhelpful thoughts.

How we think about something influences how we feel about it and consequently how we act or behave. Therefore it is important to recognise our emotions, notice our thoughts and understand how thoughts affect feelings and feelings affect behaviour (Rotter 1966, Beck 2016). Consequently, how we perceive or interpret a situation will affect how we feel about it.

Self-efficacy is being able to exert a degree of control over our thoughts, feelings and actions (Rotter 1966). By increasing self-efficacy, anxiety levels reduce with CBT style support. This is where unhelpful thoughts, that lead to negative feelings and behaviours, are noticed, challenged and reframed. (Gaudiano & Herbert 2007, Beck 2016, Roick & Ringeisen 2016).

In the study, the participants talked about how these strategies will not stop unhelpful thoughts but will help them notice and change them to more helpful thinking.

Helping children reframe negative thoughts : Mentally Healthy Schools

Being optimistic and hopeful can enable young people to persevere through challenges and manage the difficulties they face. Hope or hopeful thinking is not wishful thinking or purely optimism but the process of thinking about our goals. Together with the motivation and growth mindset, or agency, to move toward those goals, and, the metacognitive thinking and strategies to achieve those goals. (Snyder et al 2002).

Be kind, accept difference in myself and others.

It is important for our self-acceptance not to be dependent on achievement or failure and not to come from comparison to others. Young people need to grow up in an environment where diversity and difference is celebrated and modelled.

As demands on their mental health increase with their education, relationships and physical well-being it is important young people know to look after themselves. Eating well, getting plenty of exercise and sleep, as well as nurturing good friendships, taking time to relax and talk to someone if necessary.

Looking after yourself – YoungMinds

Others can help me, who can I talk to?

Self-advocacy develops independence and self-esteem for any young person, therefore essential for those with a specific learning difference (Reid 2016). Self-advocacy is the ability to identify, articulate and communicate feelings and needs. This includes understanding and acceptance of one’s own specific learning difference and needs; knowing their profile of strengths and weaknesses and what learning strategies work for them; and, being able to ask for help, for example, a different strategy or access arrangements.

Talking to someone about worrying thoughts or a difficult situation is so important for young people as for adults. It can help make sense of thoughts or a situation or just provide support to cope.

Talking Mental Health : Mentally Healthy Schools

What can I change or control in this situation and what can’t be changed?

The belief we have concerning our control over life events is also known as ‘Locus of Control’ (Rotter 1966). Agency is where the learner takes an active role in the learning process. Together with a belief that their attitude and thinking about learning will make a difference for them. By teaching and supporting young people to develop a positive internal locus of control they will have the thinking needed to help overcome the difficulties they face (Burden 2005). Praising effort and perseverance is important together with helping them attribute outcomes to those factors within their control (Seligman 2018, Dweck 2006).

Helping our young people know that they can control how they think, feel and act but they can’t control how others think, feel or act or difficult situations happening. They can though, focus on calming strategies, helpful thinking, being thankful, talking to someone and asking for help if necessary.

Teaching these resilience and coping skills explicitly develops attitudes and behaviours to strengthen a young person’s academic self-concept. So enabling them to go forward in their learning and life, generally in a better position to manage anxiety and face difficulties and challenge.

References

Bandura, A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York. WH Freeman

Beck, A. T. (2016) Cognitive Therapy: Nature and Relation to Behaviour Therapy. Behaviour Therapy 47:6 p 776-784

Burden, R.L. (2005) Dyslexia and Self-concept: Seeking a Dyslexic Identity. London: Whurr Publishers

Charteris, J. (2013) Learner Agency: A Dynamic Element of the New Zealand Key Competencies. Teachers and Curriculum, 13 p19-25

Dweck, C.S. (2006) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. The Random House Publishing Group

Everson, H.T., Smodlaka, I. & Tobias, S. (1994) Exploring the relationship of test anxiety and metacognition on reading test performance: a cognitive analysis. Anxiety, Stress, Coping. 7. P 85–96

Gaudiano, B. A., & Herbert, J. D. (2007). Self-efficacy for social situations in adolescents with generalized social anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 35.2 p 209–223

McEwen, B.S. & Morrison, J.H. (2013) The Brain on Stress: Vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course. Neuron 79.1 p404-406

Moran, T. P. (2016) Anxiety and working memory capacity: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 142:8, Aug, p 831-864. American Psychological Association

Reid, G. (2016) Dyslexia: A Practitioner’s Handbook. Chichester, Wiley.

Roick, J. & Ringeisen, T. (2016) Self-efficacy, test anxiety, and academic success: A

longitudinal validation. International Journal of Educational Research. 83 p 84-93

Rotter, J. (1966) Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, Vol 80:1 p 1-28. American Psychological Association.

Seligman, M. (2018) The Optimistic Child London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing

Sneyder, C.R. (2000) Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures and Applications. London. Academic Press

Tugade, M.M. & Fredrickson, B.L. (2004) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. American Psychological Association. 86:2, p. 320-333.

This is amazing. Thanks for sharing your rainbow.